Animism and Abrahamic religions

This series of essays was generated with Google Gemini

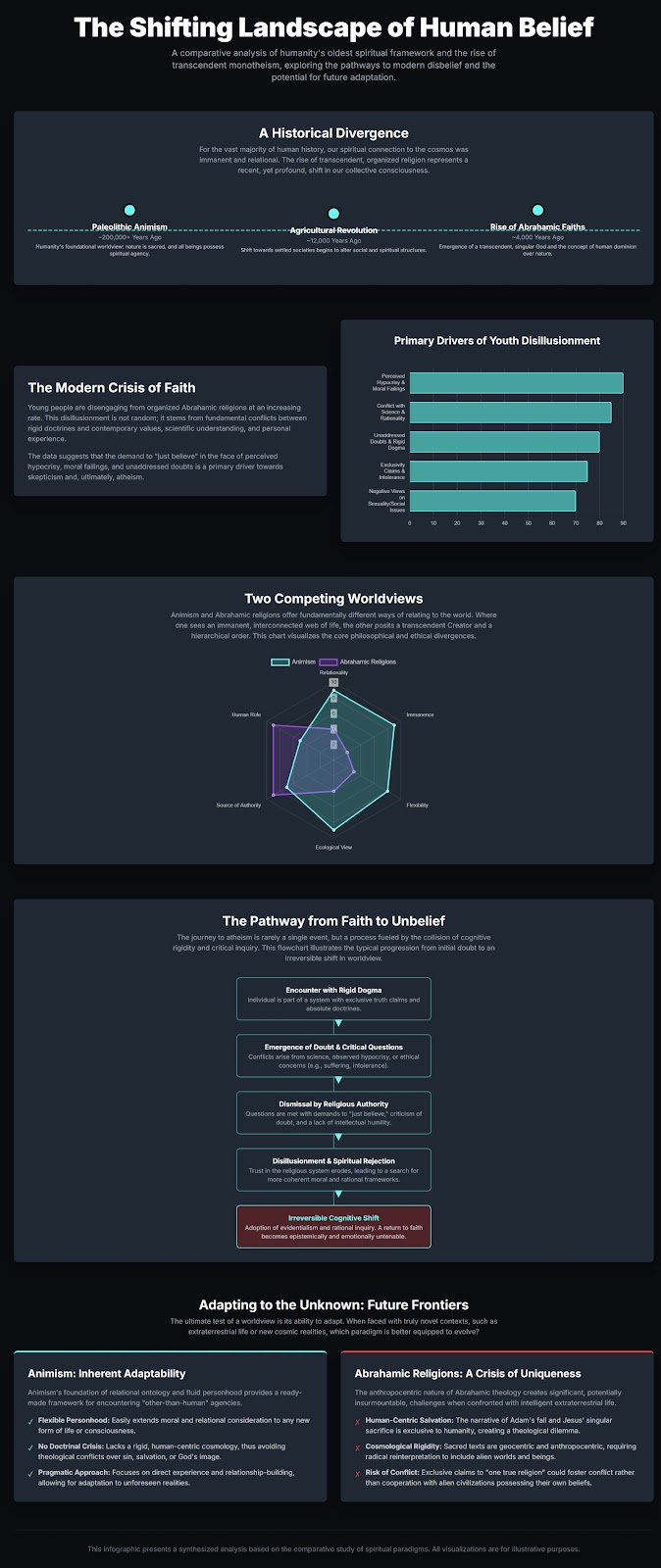

Overview

Full text

I. Introduction: Setting the Spiritual Landscape

The trajectory of human spiritual history is a complex tapestry woven from diverse belief systems, each offering unique interpretations of existence, divinity, and humanity's place within the cosmos. This report undertakes a comparative analysis of two foundational spiritual paradigms—animism and Abrahamic religions—and explores their intricate relationship with the emergence and persistence of atheism. By examining their historical development, core tenets, and adaptive capacities, a deeper understanding of their influence on human society, ethics, and potential future challenges can be discerned.

Defining Animism: Ancient Roots and Contemporary Interpretations

Animism, derived from the Latin word 'animus' meaning 'spirit' or 'soul,' is widely recognized as the world's oldest form of religious belief, deeply embedded in numerous indigenous cultures and predating the rise of classical religions. At its core, animism posits that all elements of the natural world, encompassing animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather phenomena, and even inanimate objects or abstract concepts like words, possess a distinct spiritual essence, consciousness, or agency.1 This worldview fundamentally emphasizes the interconnectedness of all living things, viewing them as interdependent parts of a single cosmos.

Early anthropological interpretations, notably by Sir Edward Tylor in 1871, defined animism as the "general doctrine of souls and other spiritual beings". Tylor theorized that these beliefs originated from early humans' attempts to explain phenomena like dreams and trances, positioning animism as a "mistake" within an evolutionary framework of religion that would eventually yield to scientific rationality. However, contemporary scholarship, often referred to as "New Animism," has largely discredited Tylor's colonialist and dualistic interpretations. This modern perspective reframes animism not as a set of literal beliefs in "spooky nature spirits" but as a "relational epistemology" and a "way of being" that prioritizes relationships, respect, and responsibility towards all life.

Defining Abrahamic Religions: Core Tenets and Historical Trajectories

The Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—represent a distinct spiritual lineage, all tracing their origins to the patriarch Abraham and sharing a foundational belief in a single, exclusive, transcendent God. This divine entity is conceptualized as eternal, omnipotent, omniscient, benevolent, and just, serving as the ultimate creator of the universe. A defining characteristic is the understanding of God as existing outside of space and time, yet simultaneously being personal and intimately involved in creation.

Central to Abrahamic faiths are concepts of divine revelation, communicated through sacred texts such as the Torah, Bible, and Quran, which provide guidance for human conduct and moral accountability. The pursuit of salvation or transcendence within these traditions is typically achieved through pleasing God and adhering to divine law.14 A notable distinction from animistic worldviews is the emphasis on a separation between the individual, God, and nature, with humanity frequently granted "dominion" over the Earth.

The Spectrum of Atheism: Historical and Philosophical Contexts

Atheism, broadly defined, signifies an absence or explicit rejection of belief in the existence of deities. Philosophical atheistic thought has a long history, with roots in ancient Greece and India, where thinkers like Xenophanes and Epicurus questioned divine causality or existence. The term "atheism" as a self-identified belief, specifically referring to disbelief in the monotheistic Abrahamic God, gained prominence in late 18th-century Europe.

Arguments supporting atheism often include the perceived lack of empirical evidence for a divine being, the philosophical problem of evil and suffering in a world supposedly governed by an omnibenevolent God, inconsistencies found within religious revelations, the argument from nonbelief, and the overarching framework of scientific naturalism. More recently, the "New Atheism" movement, gaining traction in the 21st century, has adopted a more polemical stance, asserting that faith unsupported by evidence is inherently foolish and potentially harmful, thereby advocating for a diminished respect for religious belief in society.

This report will delve into the intricate relationships between these spiritual and non-spiritual worldviews, analyzing how the inherent characteristics of Abrahamic faiths may contribute to forms of atheism that are difficult to reverse, exploring the potential of animism as a spiritual alternative for young people, examining the historical divergence between humankind's animistic nature and Abrahamic traditions, and assessing the adaptive capacities of both paradigms in confronting unfamiliar environments, such as those encountered in space exploration.

II. The Paradox of Rigidity: Abrahamic Religions and Irreversible Atheism

The inherent characteristics of Abrahamic religions, particularly their emphasis on exclusivity and absolute truth claims, can paradoxically contribute to a form of atheism that proves difficult to reverse for many individuals. This phenomenon is often rooted in the perceived conflict between rigid religious doctrines and modern understandings of science, morality, and individual autonomy.

The Exclusivity and Absolute Claims of Abrahamic Monotheism

Abrahamic religions are founded upon strict monotheism, asserting the worship of a singular, exclusive God. This theological stance frequently leads to claims of possessing the sole, ultimate truth, which can foster an "us versus them" mentality when confronted with differing belief systems. Historically, Christianity and Islam, as universalizing religions, have pursued missions to convert all humanity, a drive that has, in various periods, led to violent conflict and intolerance against those outside their fold. While Judaism does not actively proselytize, its historical texts indicate severe punishment for Israelites who worshipped other deities. Even within the Abrahamic family, internal doctrinal rigidities, such as the Christian doctrine of the Trinity, can conflict with the strict monotheistic concepts of Judaism and Islam, further illustrating the pervasive nature of exclusivity.

Critiques of Abrahamic Rigidity: Conflict with Science, Moral Failings, and Hypocrisy

The rigidity of certain Abrahamic doctrines and practices has drawn significant criticism, contributing to disillusionment and, in some cases, a definitive rejection of faith.

- Conflict with Science: A prominent critique arises from the perceived conflict between religious tenets and scientific discoveries. For instance, the literal interpretation of the Genesis creation myth often clashes with evolutionary biology, and the complexity of DNA is sometimes presented by adherents as evidence for a purposeful designer, a claim that stands in tension with scientific consensus on undirected evolution. When scientific explanations offer more parsimonious or empirically supported accounts of natural phenomena, individuals may find it increasingly difficult to reconcile these with literal religious narratives.

- Moral Failings and Hypocrisy: Historical and contemporary instances of religious violence, including the Crusades, sectarian conflicts, and acts of terrorism, are frequently cited as evidence of the harmful societal impact of religion. Beyond large-scale conflicts, specific practices such as child marriage, honor killings, genital mutilation, and the condemnation of homosexuality are highlighted as morally problematic. Furthermore, the organizational structures of some Abrahamic faiths, particularly hierarchical ones like the Catholic Church, have been implicated in systematic cover-ups of abuse, leading to significant financial and social repercussions. Even decentralized systems, while lacking coordinated tracking, face similar issues. Critics also contend that theistic religions can devalue genuine human compassion, suggesting that actions are motivated by fear of divine punishment rather than inherent empathy.

Disillusionment and Spiritual Rejection: Pathways to Atheism

The critiques outlined above, coupled with internal struggles, create significant pathways to atheism, particularly among younger generations. Young people frequently disengage from organized Abrahamic religions due to a sense that their faith was never truly their own, but rather an inherited tradition. They often witness pervasive hypocrisy among believers and leaders, where stated values do not align with observed behaviors. A lack of genuine spiritual grounding, inadequate discipleship, and an environment where questions and doubts are dismissed rather than addressed legitimately, further contribute to this disillusionment. Ethical concerns, especially around issues like sexuality, the exclusivity of religious claims, or concepts of divine judgment, often lead to a perceived gap between lived suffering and simplistic theological answers. In such contexts, the dominant cultural narratives of pluralistic tolerance and secular rationalism frequently appear more compelling or appealing.

A significant contributing factor is the presence of cognitive rigidity, which is often linked to literal interpretations of religious texts and religious fundamentalism. This rigid cognitive approach tends to establish "harsh boundaries" and reinforce an "us versus them" mentality. When young people express doubts, a rigid religious environment may simply criticize their questioning and demand "just believe". This absence of intellectual humility and cognitive flexibility within the religious community can prevent meaningful engagement with their concerns, leading to isolation and withdrawal. The inability to reconcile complex societal issues or personal suffering with overly simplistic theological answers pushes individuals towards worldviews that offer more nuanced or rational explanations.

The "Irreversible" Nature of Atheism: Philosophical Arguments and Cognitive Shifts

The transition to atheism, for many, is not a fleeting rebellion but a profound and often irreversible transformation of worldview. This shift is frequently described as a "final straw in an already long-term process," where individuals gradually realize they no longer hold belief, rather than experiencing a sudden, singular moment of disbelief. This suggests a fundamental reshaping of their cognitive and existential framework.

Atheism, as a conscious rejection of theism, is often predicated on philosophical arguments such as the problem of evil, the lack of compelling evidence for God's existence, or the parsimony of naturalistic explanations. The perceived irreversibility can stem from a deep cognitive commitment to evidentialism and rational inquiry, where religious propositions are subjected to the same skepticism as any other unproven claim. Once an individual adopts this rational framework, reverting to a belief system that is perceived as contradictory to reason or lacking verifiable evidence becomes epistemically challenging and emotionally unappealing. This process is sometimes described as a "deconstruction of faith," which modern culture often welcomes and validates.

The emphasis on exclusive monotheism and universalizing missions, inherent to Abrahamic faiths, positions other belief systems as inherently "wrong" or "false". This "us versus them" mentality, often reinforced by cognitive rigidity within some religious interpretations, can manifest as intolerance, persecution, and conflict. When individuals, particularly youth, are exposed to the pluralism of modern societies and the compelling arguments of secular rationalism, this exclusivism becomes a significant ethical and intellectual hurdle. The perceived moral failings of religious institutions—such as historical violence, child marriage, condemnation of LGBTQ+ individuals, or systematic abuse cover-ups—further erode trust and render the demand to "just believe" deeply unsatisfying. This leads to a fundamental questioning of the religion's credibility and a search for personal integrity. The transformation into atheism then becomes profound, rooted in a cognitive shift towards evidentialism and critical thinking. Once this rational framework is adopted, returning to a belief system perceived as contradictory to reason or morality becomes epistemically difficult and emotionally unappealing. This suggests that the very strength of Abrahamic religions—their absolute truth claims—becomes a vulnerability in an increasingly pluralistic, scientifically-informed, and ethically-conscious global society. The "irreversibility" implies a deep-seated worldview transformation rather than a temporary rebellion, posing a significant long-term challenge to traditional religious adherence.

Furthermore, cognitive inflexibility, often linked to literal interpretations of religious texts and religious fundamentalism, correlates with prejudice towards out-groups like atheists and gay men. This rigid cognitive approach creates "harsh boundaries" and an "us versus them" mentality. When young people ask questions or express doubts, a rigid religious environment may simply criticize their doubt and demand "just believe". This lack of intellectual humility and cognitive flexibility within the religious community prevents legitimate engagement with their concerns, leading to isolation and withdrawal. The inability to reconcile complex issues or suffering with simplistic theological answers pushes individuals towards worldviews that offer more nuanced or rational explanations. This suggests that the manner in which faith is practiced and defended, particularly its openness to critical inquiry and diverse perspectives, is a critical factor in retaining adherents and preventing irreversible spiritual rejection. The rigidity of some Abrahamic interpretations may inadvertently accelerate the path to atheism by creating an unwelcoming intellectual and emotional environment for questioning minds.

| Abrahamic Tenet/Characteristic | Corresponding Critique/Disillusionment | Pathway to Atheism |

|---|---|---|

| Strict Monotheism/Exclusivity | "Us vs. Them" Mentality/Intolerance | Rejection of exclusive truth claims, Ethical concerns |

| Transcendent God | Conflict with Scientific Discoveries | Inability to reconcile faith with scientific evidence |

| Divine Revelation (Scriptural Inerrancy) | Internal Inconsistencies in Scripture | Loss of trust in religious authority, Unaddressed doubts |

| Human Dominion over Nature | Environmental Exploitation/Desacralization | Search for alternative moral frameworks, Ecological concerns |

| Hierarchical/Centralized Authority | Hypocrisy/Abuse Cover-ups | Loss of trust in religious authority, Ethical concerns |

| Emphasis on Fear/Punishment | Devaluation of Human Compassion/Morality | Search for alternative moral frameworks |

III. Animism as Spiritual Recourse: Addressing Youth Disillusionment

In an era marked by rapid societal change, ecological crises, and a growing skepticism towards established institutions, many young people are experiencing profound disillusionment with organized religions, particularly Abrahamic faiths. In this context, animism, with its distinct worldview and relational approach, presents a compelling spiritual recourse.

Reasons for Youth Disillusionment with Organized Religion

As previously discussed, a significant number of young individuals are disengaging from organized religion for a multitude of reasons. Often, their inherited faith was never truly internalized or made their own, leading to a superficial adherence that crumbles under scrutiny. Pervasive hypocrisy among believers and leaders, where actions contradict professed values, severely erodes trust and credibility.34 Many young people report a lack of genuine spiritual grounding or discipleship, feeling left to "figure it all out" on their own, making them vulnerable to external influences.34 A critical factor is the failure of religious communities to legitimately hear and address their questions and doubts, frequently met instead with admonitions to "just believe".

Furthermore, ethical concerns, particularly regarding issues of sexuality, the exclusivity of religious claims, or the concept of divine judgment, often create an insurmountable moral dilemma. A perceived disconnect between their lived experiences of suffering and the simplistic theological answers offered by religious institutions further exacerbates this disillusionment. In an increasingly pluralistic and secular world, the dominant cultural narratives of tolerance and rationalism often appear more convincing and appealing than traditional religious narratives. Young people are also acutely aware of the historical atrocities committed in the name of God and the pressing urgency of planetary ecological crises, issues that traditional religions may not adequately address or even be seen as contributing to.

Core Principles of Animism: Interconnectedness, Relationality, and Respect for Nature

Animism offers a stark contrast to the hierarchical and often anthropocentric views of organized religions. It fundamentally asserts that all objects, places, and creatures possess a distinct spiritual essence or consciousness, emphasizing the profound interconnectedness of all things. This includes not only humans but also animals, plants, rocks, rivers, weather patterns, and even celestial bodies. Within this worldview, spirits and humans are considered interdependent parts of a single cosmos, fostering a deep sense of kinship and mutual respect for nature. Humanity is perceived as an integral component of the natural world, not separate from or superior to it, bearing a fundamental responsibility to maintain balance and harmony within this intricate web of life.

Animistic practices frequently involve rituals, offerings, and direct communication with spirits to seek guidance and preserve harmony. Shamanism, a spiritual practice closely associated with animism, features shamans who serve as spiritual guides and healers, facilitating communication between the human and spirit worlds. While classical definitions of animistic ethics might suggest a pragmatic and relativistic focus on immediate, practical benefits, lacking the absolute laws seen in Abrahamic traditions, contemporary "New Animism" scholarship emphasizes the inherent relationships and responsibilities that define animistic ways of being.

How Animism Offers Spiritual Alternatives: Ecological Frameworks, Mental Well-being, and Direct Experience

Animism provides a compelling framework that addresses many of the contemporary spiritual and existential challenges faced by youth.

- Ecological Frameworks: Animism offers a profound lens through which to understand humanity's place in a living cosmos, directly challenging the mechanistic view of nature as merely a resource to be exploited. It cultivates deep respect and reverence for the environment, actively encouraging sustainable living practices, mindful resource utilization, and a strong sense of stewardship as caretakers of the land. This aligns seamlessly with modern ecological thought and concepts like Gaia theory, presenting a "spiritual ecology" that is increasingly recognized as vital for addressing climate change and fostering a regenerative culture for the future.

- Mental Well-being: From a psychological perspective, engaging with an animistic worldview can involve a process of "turning down" conventional cognitive functioning to "hear" the intrinsic "inner monologue" of the world, thereby connecting individuals with the preconscious wisdom of their own psyche and the natural environment. Participation in intentional ritualistic behaviors—such as art-making, dance, or storytelling—can facilitate the integration of emotional and preconscious aspects of the psyche, promoting psychological healing and growth. This relational worldview helps to overcome feelings of anxiety, separation, and abstraction, fostering a profound sense of awe and reverence for life.

- Direct Experience and Adaptability: Animism places a strong emphasis on direct spiritual experience, encouraging individuals to seek personal connections with spirits through rituals, visions, and dreams. Unlike many organized religions, animistic societies typically lack centralized authority or rigid creeds, which allows for highly individualized and adaptable spiritual experiences. This inherent flexibility permits animism to coexist with and even merge into other religious traditions, demonstrating its capacity for syncretism and resilience.

The "New Animism" and its Contemporary Relevance for Modern Challenges

The emergence of "New Animism" in contemporary scholarship represents a reinterpretation of the concept as a relational approach to the world, actively striving to overcome dualistic constructions such as subject-object or nature-culture. This modern understanding acknowledges "other-than-human agencies" and fosters an "intersubjective" reality where meaning is continuously constructed through engagement and communication with all beings.

This revised approach resonates powerfully with contemporary philosophy of religion, nature-based spiritualities, and environmental activism. It is seen as a "subversive attempt to decolonize the hegemonic tradition" of Western thought, which has historically marginalized animistic worldviews. By recognizing personhood in non-humans, this framework facilitates the establishment of moral relationships with the non-human world, offering a path to re-enchantment and a more holistic engagement with existence.

Youth disillusionment often stems from the perceived failures of a transcendent, externalized God to intervene in suffering or provide relevant moral guidance. The Abrahamic model of a judging, external God to whom nature and individuals are subordinate 14 contrasts sharply with animism's view of a world permeated by spiritual beings and forces. Animism offers an immanent spiritual path, where the sacred is found within the natural world and relationships with it. This immanence may resonate more deeply with modern scientific understandings of interconnected ecosystems and human psychology, providing a spiritual framework that does not require a radical separation from the physical world or a belief in an aloof deity. This suggests that animism is not merely an "alternative" but potentially a remedy for a spiritual void created by the perceived limitations of transcendent monotheism in a secular, scientific age. It offers a path to re-enchantment with the world that aligns with ecological consciousness and a desire for direct, lived spiritual experience, addressing the "spiritual but not religious" trend prevalent among many young people today.

Moreover, young people are often alienated by the rigid doctrines, hierarchical structures, and "us vs. them" mentalities prevalent in some organized Abrahamic religions.29 Animism, by contrast, is characterized by its lack of elaborate organization, required creed, and centralized authority. Its emphasis on "relational epistemology" and "fluid personhood" 7 means it is inherently adaptable to diverse experiences and contexts. The ongoing process of "figuring out" the ontological status of things and persons 41 and engaging in direct, individualized spiritual experiences 2 provides a flexible framework that can accommodate new insights and personal journeys. This stands in contrast to Abrahamic faiths where divine revelation is often seen as fixed and external.14 This highlights that the inherent flexibility and relational nature of animism make it uniquely suited to address the dynamic and complex challenges faced by contemporary youth, including rapid cultural change and the profound need for personal meaning-making in a pluralistic world. Spiritual systems that prioritize adaptable, lived experience over fixed dogma may prove more resilient and appealing in the modern era.

| Reason for Youth Disillusionment (Abrahamic) | Animistic Recourse/Benefit |

|---|---|

| Hypocrisy/Moral Failings | Emphasis on Ethical Action/Responsibility |

| Unaddressed Questions/Doubts | Openness to Direct Experience/Individual Interpretation |

| Exclusivity/Intolerance | Inclusivity/Relationality with All Beings |

| Disconnection from Nature/Ecological Crisis | Deep Connection to Nature/Ecological Stewardship |

| Lack of Personal Ownership/Rigid Dogma | Flexible "Ways of Being"/No Centralized Creed |

| Simplistic Answers to Suffering | Holistic Integration of Psyche/Natural World |

| Isolation/Lack of Community | Sense of Kinship/Interdependence with All Life |

IV. A Historical Divergence: Humankind's Animistic Nature vs. Abrahamic Worldviews (Last 200,000 Years)

The spiritual journey of humanity, spanning hundreds of thousands of years, reveals a profound shift from an inherently animistic relationship with the world to the more structured and transcendent paradigms of Abrahamic religions. This historical divergence has had far-reaching implications for humanity's perception of nature, the divine, and its place within the cosmos.

The Deep History of Human Spirituality: Paleolithic Animism as a Foundational Worldview

Animism is widely acknowledged as the earliest form of human spirituality, with evidence of animistic belief systems extending as far back as the Paleolithic era. Prehistoric animistic practices are often associated with shamanic traditions, manifest in cave paintings, and indicated by burial sites, all suggesting that early humans held a belief in the spiritual essence of animals and the natural world. Edward Tylor, despite the criticisms leveled against his evolutionary framework, posited that the universal human experiences of dreams and trances provided a basis for the widespread existence of religion, with animism representing its most primitive form. This ancient worldview fostered a deep-seated respect for the environment and encouraged sustainable practices, as humans perceived themselves as an integral part of a larger, interconnected spiritual ecosystem.

The Shift from Immanence to Transcendence: Anthropological and Philosophical Perspectives

A fundamental distinction between animism and Abrahamic religions lies in their understanding of divine presence—immanence versus transcendence.

- Animism's Immanence: Animistic worldviews characteristically locate spiritual reality within the world itself. Spirits and agency are understood as inherent to natural phenomena, implying no categorical distinction between the spiritual and physical realms.5 The sacred is encountered directly in the landscape, animals, plants, and even weather patterns.

- Abrahamic Transcendence: In contrast, Abrahamic religions conceive of God as a transcendent creator, existing distinctly outside and beyond the created world. Divine revelation is seen as external to the self, nature, and established customs, originating from a God who is "above, beyond us".

- Historical Progression and Monotheistic Imposition: Tylor's discredited theory proposed a linear evolutionary progression from animism to polytheism, culminating in monotheism. He believed that animism, being a "mistake," would eventually be rejected by societies as they became more scientifically advanced. However, modern archaeological and anthropological scholarship has largely dismissed this simplistic, linear model as "unsophisticated" and "erroneous". Historically, the ancient age of atheism, which was often tolerated in polytheistic societies, came to an end with the rise of monotheistic imperial forces that demanded the acceptance of one "true" God, thereby leaving little room for disbelief. This historical trajectory suggests a forceful imposition of a transcendent divine concept over the previously prevalent immanent spiritual understandings.

Humanity's Place in Nature: Animistic Interconnectedness vs. Abrahamic Dominion/Stewardship

The contrasting views on humanity's relationship with nature represent another significant divergence.

- Animistic Interconnectedness: Animistic beliefs emphasize the deep interconnectedness and interdependence of all living things. Humans are seen as an integral part of nature, not separate from or superior to it. This worldview fosters a profound respect for the environment and actively promotes sustainable living practices, recognizing the intrinsic value of all life forms.

- Abrahamic Dominion/Stewardship: Abrahamic faiths assert a special, elevated role for humans within creation, stemming from the Genesis mandate to "have dominion" over the Earth. This concept has been historically interpreted by some as granting human supremacy and a right to exploit nature for their own ends.

- Stewardship Reinterpretation: In response to growing environmental concerns, many contemporary interpretations within Abrahamic traditions emphasize "stewardship" or "caretaker" roles, arguing that appropriate dominion necessitates caring for creation. Judaism, for example, possesses an ancient notion of stewardship, with laws protecting nature and holidays celebrating the natural world.47 Nevertheless, the fundamental theological distinction of humans being created "in God's image" and thus distinct from other animals often remains central to these interpretations.

The Desacralization of Nature and its Historical Impact

The Abrahamic emphasis on a transcendent God and humanity's divinely granted dominion over nature significantly contributed to what is termed the "desacralization of nature". This historical process involved stripping the cosmos of its inherent sacredness and meaning, progressively reducing knowledge to purely rational and empirical domains. Critics argue that Christianity, by challenging nature-based religions and establishing a dualistic separation between humanity and nature, inadvertently facilitated the exploitation of the natural world. This anthropocentric viewpoint is frequently identified as a root cause of contemporary ecological crises. The broader shift in focus from a sacred cosmos to a secular order, and from a God-centered worldview to one centered on human beings (humanism), further propelled this desacralization, impacting value systems, thought processes, and even the structure of human emotions.

The historical shift from an animistic worldview, where humans are deeply embedded within a sacred, interconnected natural world, to the Abrahamic model of a transcendent God and human "dominion" represents a profound ontological rupture. This "desacralization of nature" allowed for a conceptual separation of humanity from the environment, paving the way for exploitation rather than stewardship. The perceived superiority of humans, understood as being "made in God's image" over non-human life, further justified an instrumental view of nature. This historical divergence suggests that the current ecological crisis is not merely a technological or economic problem, but deeply rooted in a fundamental shift in human spiritual and philosophical orientation towards the natural world. It implies that addressing environmental challenges may necessitate a re-evaluation of foundational anthropocentric assumptions and a return to more immanent, relational understandings of nature.

Furthermore, the transition from diffuse, flexible animistic practices to organized, often hierarchical Abrahamic religions 33 coincides with the rise of more complex societies and imperial forces. The demand for acceptance of "one true God" and the establishment of "absolute laws or principles" provided a framework for social control and unity that was less present in the pragmatic, relativistic ethics of animism. The "desacralization of knowledge" by reducing it to rational and empirical domains, while fostering scientific progress, also served to centralize authority and define "truth" in a way that could be controlled and propagated by religious institutions. This highlights a potential causal link between the theological shift from immanence to transcendence and the development of more rigid, centralized societal structures. The "rigidity" of Abrahamic religions, therefore, might not just be a theological characteristic but also a socio-political tool that emerged to manage and control increasingly complex human populations, leading to both large-scale societal organization and, paradoxically, the seeds of its own rejection when those structures fail or are perceived as oppressive.

| Dimension | Animistic View | Abrahamic View |

|---|---|---|

| Divine Presence (Immanence/Transcendence) | Immanent (Spirits within nature) | Transcendent (God external to creation) |

| Human-Nature Relationship | Interconnected/Part of Nature | Dominion/Stewardship over Nature |

| Source of Spiritual Authority | Direct Experience/Shamans | Divine Revelation (Scripture/Prophets) |

| View of Non-Human Entities | All things possess spiritual essence/agency | Humans distinct/superior |

| Ethical Framework | Relativistic/Pragmatic but emphasizing respect/responsibility | Absolute Laws/Moral Accountability |

| Historical Prevalence | Paleolithic origins/Indigenous cultures | Post-Animistic/Organized Religions |

V. Adapting to the Unfamiliar: Animism, Abrahamic Religions, and Extraterrestrial Environments

The prospect of encountering unfamiliar environments, particularly celestial bodies beyond Earth or intelligent extraterrestrial life, presents a compelling thought experiment for assessing the adaptive capacities and inherent limitations of different spiritual paradigms.

The Adaptive Potential of Animism: Relational Ontology and Flexible Personhood in Unfamiliar Contexts

Animism, with its core tenet that all material phenomena possess agency and that there is no categorical distinction between the spiritual and physical world, offers a potentially highly adaptive framework for navigating unfamiliar environments. This worldview acknowledges and fosters an "ecology of other-than-human agency", emphasizing intersubjectivity—a direct subject-to-subject sharing of presence—and a "fluid and unstable" concept of personhood that emerges from ongoing communicative processes.

In an animistic framework, "to be a person... is a very flexible way of existence and one has to learn to know what the different personhoods are about". This inherent flexibility and focus on discerning and relating to diverse forms of personhood, even in non-biological phenomena, makes animism uniquely suited to encountering unfamiliar environments or intelligent extraterrestrial life. The pragmatic orientation of animists, who, when a remedy fails, "keep thinking 'maybe next time it will work'" and are justified in seeking alternative solutions, further suggests an inherent adaptability to novel and unexpected situations. Moreover, animism facilitates the recognition of personhood in non-humans, thereby enabling the formation of moral relationships with the non-human world. This ethical extension beyond Earth's familiar life forms suggests a pre-existing framework for ethical engagement with vastly different forms of life, including potential extraterrestrial beings.

Limitations of Abrahamic Religions in Extraterrestrial Scenarios: Theological Challenges (Sin, Salvation, Cosmology)

The human-centric nature of Abrahamic theology presents significant challenges when contemplating intelligent extraterrestrial life (ETL). Abrahamic religions generally assert that humans are distinct from animals, created in God's image, and endowed with free will and a capacity for sin. The foundational narratives of sin and salvation are deeply anthropocentric, revolving around Adam's fall and Jesus's singular, redemptive sacrifice for humanity.

The existence of intelligent ETL raises profound theological questions that challenge these core doctrines. Would these extraterrestrial beings be subject to Adam's sin? Would they require redemption, and if so, would a separate, equivalent salvific figure be necessary for each intelligent species across the cosmos? The concept of multiple Christs, for instance, is considered heretical in mainstream Christianity. While some Abrahamic adherents argue that the existence of ETL would not limit God's omnipotence, it could nonetheless "mess with Abrahamic cosmology". The biblical focus on Earth and its inhabitants, with some interpretations suggesting that only "creatures on EARTH go to heaven", might struggle to integrate alien life without substantial reinterpretation of sacred texts. Furthermore, the monotheistic exclusivity and claims of "one true religion" inherent to Abrahamic faiths could lead to significant conflict if humanity were to encounter alien civilizations possessing their own distinct spiritual or religious beliefs. Historical precedents of human cultures meeting, often resulting in the destruction of the contacted civilization, suggest a potential for negative outcomes in such extraterrestrial encounters.

Potential for Adaptation and Reinterpretation within Abrahamic Traditions

Despite these formidable challenges, religious traditions have historically demonstrated remarkable resilience and capacity for adaptation. Religions are often described as "resilient buggers" that would likely "change and adapt like every other living thing does," with some branches potentially falling away while new ones emerge. From a Jewish perspective, denying the possibility of extraterrestrial life would be controversial, as it could be seen as an attempt to limit God's boundless capabilities. Similarly, Islam teaches that God's powers extend beyond human imagination and that He has spread living creatures throughout both the heavens and the Earth. Theological discussions within Abrahamic faiths have already begun to grapple with the implications of ETL, with some theologians exploring how concepts of grace and redemption might extend to non-human intelligent beings.

Animism's fundamental premise of "fluid personhood" and the recognition of "other-than-human agencies" means it already operates within a framework that readily accommodates diverse forms of intelligence and consciousness beyond the human. This stands in stark contrast to Abrahamic anthropocentrism, where humans are uniquely created in God's image and granted dominion. In a future where humanity might encounter vastly different forms of life or even intelligent beings on other planets, animism's relational ontology provides a pre-existing conceptual toolkit for understanding and ethically engaging with these new "persons" without requiring a complete overhaul of its core tenets. The inherent "effort to maintain personhood" in animism implies an ongoing process of understanding and adapting to new forms of being, which is inherently suited for unfamiliar environments. This suggests that animism, far from being a "primitive" belief, offers a highly sophisticated and adaptable metaphysical framework that may be more congruent with a future of space exploration and potential extraterrestrial contact than the human-centric and Earth-bound narratives of traditional Abrahamic faiths. It positions animism as a potentially futuristic spiritual model.

Conversely, the Abrahamic emphasis on humanity's unique creation in God's image, Adam's singular sin, and Jesus's unique sacrifice for human salvation creates a "crisis of uniqueness" when confronted with intelligent extraterrestrial life. If aliens exist, are they also created in God's image? Do they have souls? Did they fall from grace, and if so, how were they redeemed? The idea of Jesus dying multiple times for multiple species is theologically problematic. This forces Abrahamic traditions into a dilemma: either limit God's creation to Earth (a notion some adherents reject as limiting God's power), or undertake radical theological reinterpretation of core doctrines of sin, salvation, and Christology to accommodate non-human intelligent life. While the "resilience" of religions suggests adaptation, the depth of this doctrinal challenge is significant. This highlights that the limitations of Abrahamic religions in extraterrestrial contexts are not merely practical but deeply theological, challenging the very foundations of their salvific narratives and human-divine relationship. The encounter with ETL could force a profound re-evaluation of anthropocentric theology, potentially leading to schisms or the emergence of entirely new theological interpretations that either expand or fundamentally alter existing doctrines.

| Dimension | Animistic View | Abrahamic View |

|---|---|---|

| Core Ontological View | Relational/Intersubjective cosmos | Transcendent God, human-nature separation |

| Concept of "Personhood" | Flexible, fluid, includes non-humans | Human-centric (made in God's image, free will) |

| Relationship with "Other-than-Human" | Direct engagement, moral relationships | Dominion/Stewardship over Earth's life |

| Flexibility/Adaptability | Highly adaptable, pragmatic | Rigid doctrines, fixed revelation |

| Theological Implications of ETL | Easily integrates new forms of life/agency | Challenges to sin/salvation narratives |

| Ethical Approach to ETL | Extends kinship/respect to all beings | Potential for conflict due to exclusivity |

VI. Conclusion: Synthesis and Future Spiritual Pathways

The comparative analysis of animism and Abrahamic religions reveals distinct spiritual paradigms with profound implications for human belief, societal development, and future adaptation. The journey from humanity's deep animistic roots to the rise of organized monotheistic faiths, and the subsequent emergence of atheism, illuminates a complex interplay of historical, philosophical, and sociological forces.

The rigidity and exclusivity inherent in some interpretations of Abrahamic religions contribute significantly to a form of atheism that is difficult to reverse. The emphasis on singular truth claims, often leading to an "us versus them" mentality, coupled with perceived conflicts with scientific advancements, moral failings, and hypocrisy within religious institutions, drives many individuals, particularly youth, to profound disillusionment. The inability of rigid religious frameworks to adequately address complex questions or reconcile suffering with simplistic answers pushes individuals towards rational, evidentialist worldviews, making a return to traditional faith epistemically challenging. This suggests that the very strength of Abrahamic religions—their claim to absolute truth—becomes a vulnerability in an increasingly pluralistic and scientifically informed global society.

Conversely, animism offers a compelling spiritual recourse for those disillusioned with traditional organized religions. Its core principles of interconnectedness, relationality, and deep respect for nature provide a spiritual ecology that resonates with modern environmental consciousness and a desire for holistic well-being. The immanent nature of animistic spirituality, where the sacred is found within the natural world, contrasts with the transcendent, externalized God of Abrahamic faiths, potentially offering a more congruent framework for a scientific age. The inherent flexibility of animism, its lack of rigid dogma, and its emphasis on direct, individualized spiritual experience make it adaptable to diverse personal journeys and contemporary challenges, fostering a sense of kinship and responsibility towards all life.

Historically, the divergence between humanity's animistic nature and Abrahamic worldviews represents a significant ontological shift. The transition from an immanent, interconnected relationship with a sacred natural world to a transcendent God and human "dominion" contributed to the "desacralization of nature," paving the way for environmental exploitation. This historical trajectory also highlights how the development of more organized, hierarchical religious structures provided frameworks for societal control, which, while enabling large-scale organization, also laid the groundwork for future rejection when those structures are perceived as oppressive or morally compromised.

Looking to the future, particularly in the context of encountering unfamiliar environments like celestial bodies or intelligent extraterrestrial life, animism demonstrates a significant adaptive advantage. Its relational ontology and flexible concept of "personhood" inherently accommodate diverse forms of intelligence and consciousness, providing a pre-existing ethical framework for engaging with non-human entities without requiring a radical overhaul of core tenets. In contrast, Abrahamic religions face a "crisis of uniqueness," as their human-centric narratives of sin and salvation are profoundly challenged by the hypothetical existence of intelligent extraterrestrial life, necessitating deep theological reinterpretation or risking fundamental doctrinal schisms.

The implications for contemporary spiritual and societal challenges are profound. The ongoing tension between scientific rationality and religious belief, as well as the urgent environmental crisis, demand new approaches to spirituality. The insights from animistic worldviews, particularly their emphasis on relationality and ecological interconnectedness, offer valuable perspectives for enriching modern spiritual discourse and practice, even for those outside traditional religious frameworks. For Abrahamic faiths, fostering cognitive flexibility, promoting intellectual humility, and engaging transparently with ethical challenges and scientific advancements are crucial for addressing youth disillusionment and ensuring their continued relevance.

Ultimately, fostering inter-worldview dialogue and mutual respect is paramount. Moving beyond "us vs. them" mentalities and recognizing the diverse ways humanity seeks meaning and connection can facilitate a more resilient and adaptable spiritual landscape, better equipped to address shared human and planetary challenges in an increasingly complex and interconnected world.

Comments

Post a Comment